From “the shaking palsy” to drug repurposing: A look back at the history of Parkinson’s research

April 5, 2017

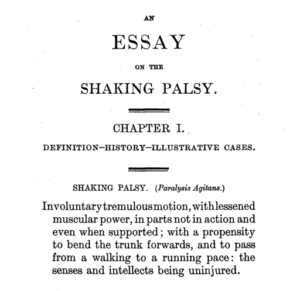

In 1817, an English surgeon named James Parkinson published An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, which described a disease that would later come to bear his name. Since then, our understanding of Parkinson’s has changed greatly and–thanks to the tireless work of scientists, physicians, advocates and people with Parkinson’s—we may be on the cusp of a seismic shift in how the disease is diagnosed and treated. In honor of Parkinson’s Awareness Month, we’re taking a look back at some of the major milestones in research and treatment.

James Parkinson pens An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, the first clinical description of what was then called paralysis agitans. In doing so, he notes historical references to the disease in ancient texts including Ayurveda as well as references from Sylvius de La Boë in 1680, among others.

1868-1881

Jean-Martin Charcot, considered to be the Father of Modern Neurology, makes several critical discoveries related to paralysis agitans, including differentiating it from other neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis. He also renamed the condition “Parkinson’s disease”.

1910

Dopamine is synthesized for the first time by James Ewens and George Barger at Wellcome Laboratories in London, England.

1912

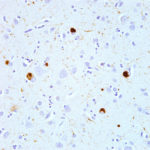

Friedrich Lewy describes the clumps of proteins found in the brains of people with Parkinson’s. These would later be named “Lewy bodies”.

1919

Constantin Trétiakoff demonstrates the link between Parkinson’s and lesions in the substantia nigra (the “black substance” in Latin), the area of the brain where dopamine-producing cells are found. He also observed that the more cells that were lost, the lighter the color of the substantia nigra.

1921

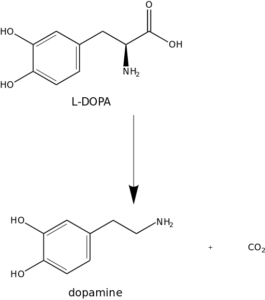

L-dopa, the precursor to dopamine, is synthesized in the lab for the first time. It previously was isolated from the bean Vicia faba in 1913 by Markus Guggenheim at Hoffmann-LaRoche. (For a full history of dopamine and L-dopa, check out Stanley Fahn’s comprehensive article here.)

1939

Hermann Blaschko and Peter Holtz separately propose a molecular pathway that described the conversion of L-dopa to dopamine. Later, in 1956, Oleh Hornykiewicz would travel from Vienna to Blaschko’s lab at Oxford, where Hornykiewicz was asked to explore the link between dopamine and blood pressure. More on that below.

1957

Kathleen Montagu of the Runwell Laboratory describes the occurrence of dopamine in the brains of humans and several other species. Other key findings about dopamine are published separately by Peter Holtz, Hans Weil-Malherbe and Arvid Carlsson (read more here, starting on page 252).

1958

Arvid Carlsson and Nils-Åke Hillarp in Sweden uncover dopamine’s function as a neurotransmitter, a molecule that is responsible for communication between brain cells. Carlsson later won a Nobel Prize for this work.

1959

Using a brain donated by a person with Parkinson’s, Oleh Hornykiewicz conducts a von Euler and Hamburg color reaction test to measure the amount of dopamine present. He would later write (check out page 256 of the link for the story):

“Instead of the pink color in the control samples, indicating the presence of dopamine, the reaction vials containing the Parkinson’s material showed hardly a tinge of pink discoloration. For the first time ever, and even before placing the reaction vials into the colorimeter, I could see brain dopamine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease literally with my own naked eye!”

1960

Oleh Hornykiewicz publishes the results of his dopamine studies, which link a loss of the dopamine in the brain to Parkinson’s disease.

1961

Oleh Hornykiewicz and Walther Birkmayer administer intravenous L-dopa to several people with Parkinson’s disease. Hornykiewicz later described the effect as “spectacular.” The first L-dopa trials began later that year. A paper outlining their findings was published in November.

1967

George Cotzias describes a method for gradually increasing the dosage of D,L-dopa (a combination of L-dopa and D-dopa) over a long period of time to mitigate the drug’s side effects, such as nausea and anorexia. He later combined L-dopa with carbidopa, which improved L-dopa’s effect while reducing side effects. Cotzias later won the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award for his work.

1969

Melvin Yahr publishes the results of a double-blind study that confirms Cotzias’ results.

1970

L-dopa is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It goes one to become the gold standard for Parkinson’s treatment and remains as such to this day. (Check out this story from the July 5, 1970 edition of The Chicago Tribune).

1982

Six people in California end up with severe parkinsonian symptoms after using a bad batch of synthetic heroin. Investigations spearheaded by Dr. J. William Langston uncover that the heroin contained a chemical known as MPTP, which selectively targets the same brain cells damaged in Parkinson’s disease. The MPTP model for Parkinson’s fuels new research, leading to a better understanding of the disease.

1987

Alim Louis Benabid conducts a procedure that would lead to deep-brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s-related tremor. DBS is a surgical procedure in which wires are implanted in a person’s brain along with a small generator in the chest. The electrical pulses help restore voluntary movement and reduce tremor in some patients. The work built on findings by Mahlon DeLong, who shifted the paradigm on how scientists thought about brain circuitry. Benabid and DeLong won the 2014 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for their discoveries.

The first cell replacement studies are conducted in Lund, Sweden. In 1990, it was determined that the procedure could reduce symptoms, leading to the idea that cell therapy could be developed one day in the future. In 2007, following the deaths of two of the patients, it was found that some of the grafted cells had survived, but were demonstrating the signs of Parkinson’s disease. This suggested that Parkinson’s may spread in a “prion-like” manner, jumping from cell to cell in the brain.

Stanley Fahn and colleagues publish the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, which helps physicians determine the severity of a patient’s disease. It was later revised to account for advances in research and treatment.

1997

Robert Nussbaum links a mutation in the gene that codes for a protein called alpha-synuclein with inherited cases of Parkinson’s, which make up less than 10 percent of all cases. Later that year, Maria Grazia Spillantini describes alpha-synuclein as the main component of Lewy bodies, clumps of proteins that are found in the brains of people with Parkinson’s.

2003

Braak Staging was developed to describe the severity of Parkinson’s pathology.

2004

The gene LRRK2 is linked to Parkinson’s disease by two papers published in Neuron.

Present day

Several drugs, many of which were originally developed to treat other diseases, have have shown promise for slowing or stopping Parkinson’s disease and are being investigated in the lab and in clinical trials. While we can’t list them all, you can read more about VARI’s work in this area and its collaboration with The Cure Parkinson’s Trust here.

Want more information? Check out these comprehensive histories:

- The medical treatment of Parkinson disease from James Parkinson to George Cotzias—Stanley Fahn (Movement Disorders)

- Four pioneers of L-dopa treatment: Arvid Carlsson, Oleh Hornykiewicz, George Cotzias and Melvin Yahr—Andrew J, Lees, Eduardo Tolosa and C. Warren Olanow (Movement Disorders)

- The history of Parkinson’s Disease: Early clinical descriptions and neurological therapies—Christopher G. Goetz (Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine)

- Milestones in 200 years of Parkinson’s disease research—Journal of Parkinson’s Disease (open-access)

- The history of neuroscience: An autobiography—Society for Neuroscience (beginning on page 240)