Each year, more than 250,000 women in the U.S. will be diagnosed with breast cancer, making it the most common cancer in women, with the exception of skin cancers.

Thanks in part to screening, early intervention and advances in treatment, the number of deaths from breast cancer dropped 39 percent between 1989 and 2015. However, that figure has largely leveled off, reinforcing the need for new treatments that help even more patients beat this devastating disease.

So, in honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’re taking a look at how some of the latest research may change the future of treatment and help women live longer, healthier lives.

Breast cancer isn’t one disease. It’s many…

Most cancers are named for the tissue or organ in which they begin. In many ways, however, that’s where the similarities end.

Often, breast cancers are divided into four major groups—luminal A, luminal B, HER2 type and triple-negative—each with their own characteristics and behaviors that inform how they progress and respond to treatment.

That’s important because what often successfully treats one type of breast cancer may not work for another.

“Cancer is very personal disease often with a high level of variation from patient to patient,” said Dr. Carrie Graveel, a senior research scientist in VARI’s Steensma Laboratory. “Better understanding how these types are different on the most basic level is critical for more precisely diagnosing patients as well as developing treatments that target their specific disease.”

…and we keep finding more

Thanks in part to large-scale efforts like The Cancer Genome Atlas, which rigorously analyze samples from hundreds of patients with different cancers, we now know more about the breast cancer than ever before.

Their results show in minute detail the vast variation between breast cancers, including additional subtypes within the generally recognized groups. In one case, the team even determined that a relatively rare subtype is so different on a molecular level that it should be considered a distinct disease.

Triple-negative breast cancer is particularly tough to treat, but research is catching up.

Although it only accounts for 15 to 20 percent of all breast cancer cases, triple-negative breast cancer is responsible for a disproportionate number of cancer-related deaths.

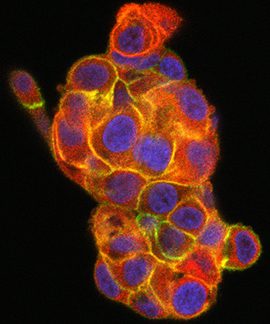

This is due, in part, to its aggressive nature and diversity of cells that make up the tumor, making it more likely than other types to recur.

It is also resistant to many existing medications because it lacks three major receptors—molecules that send and receive messages from cell to cell—that are present in other types of the disease. Cancer medications often target these receptors, which act as a sort of flag marking the cancer cell for attack. Because triple-negative tumors don’t have these receptors, they withstand many treatment strategies available to patients fighting other types of breast cancer.

But there is hope.

“Chemotherapy often is a viable option for many women with triple-negative breast cancer,” Graveel said. “We’ve also found that a well-known oncogene called MET, which is a major player is many cancers, may be a promising drug target in the majority of triple-negative breast cancers. Research is ongoing, but we are very optimistic about our early results.”

For more information on cancer screening, please visit the National Institutes of Health here.